India is the 3rd largest producer of e-waste in the world and formally recycles only 10% of it. The environmental and health hazards of unsound recycling practices, barriers to compliance with legal standards and marginalisation threaten the livelihood of unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled labourers working in this sector.

Community Design Agency was brought on board to partner with E[co]work Association International (EAI) to conceptualise and design an industrial co-working space for the informal dismantling community in the e-waste sector in North East Delhi, through a participatory and socially inclusive process. This would enable their transition and integration with the formal sector and also assess the demand for such a business plan.

I was the project lead and primary researcher for this project and spent over a year making friends and acquaintances with e-waste dismantling businessmen and community at large, residing and working in informal neighbourhoods of North East Delhi, mainly Mustafabad and Seelampur.

Working with a community that is living and working in North East Delhi gave us insights into their vulnerability beyond the informality of their businesses, into multiple social and political challenges that they continue to face. From delays due to law enforcement in those neighborhoods to communal riots, to the roadblock during farmers’ protests in India, these challenges affected their work and our engagement with them. We adapted to these challenges, even if it meant being flexible with timelines and deadlines.

Image 1: A local dismantler in Mustafabad sitting outside his workshop on a block due to lack of light and ventilation. Below him is an open sewerage.

Image 2: An open drain next to the residential units with ground-floors used as e-waste dismantling workshops in Seelampur. Credit: Ishtiaq Wani

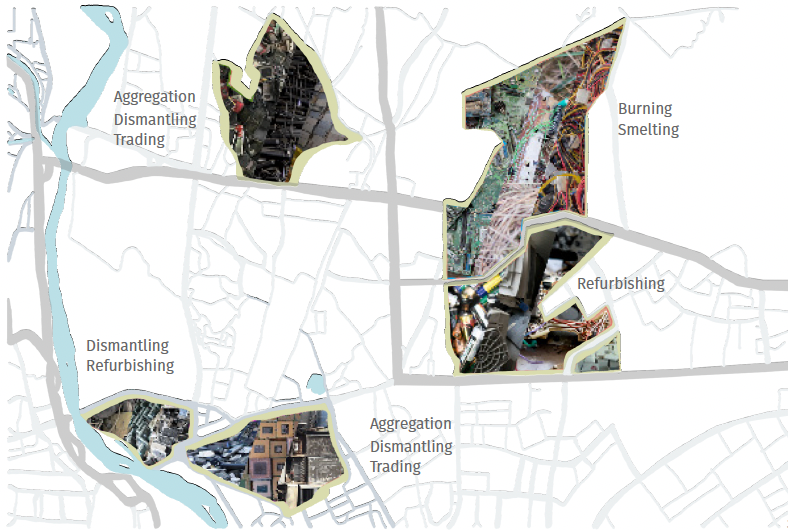

Majority of India’s e-waste is treated informally, a process which is largely concentrated in North East Delhi. With a population of over 22 lacs (2.2M) spread over 62 sq.km., North East Delhi is a mix of semi-urbanised areas and urban villages. The e-waste hub is located in the neighbourhoods of Mustafabad, Seelampur, Dilshad Garden, Mandoli and Shastri Park, each with specific core activities like dismantling, smelting, refurbishing and trading. There are over 50,000 people employed directly or indirectly in informal e-waste processing and rely on it for their daily income. Many of them have migrated from districts and cities from the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh such as Meerut, Muradabad and Budaun and belong primarily to the Muslim community

Process

It was key to first create a space where the e-waste micro-entrepreneurs and their community would be able to share their motivations and aspirations as equal stakeholders in a sector that has been running informally for decades, before we introduce any new tools. A participatory approach allows us to understand the complexity of the e-waste sector and particularly the hurdles faced by these micro-entrepreneurs. This also helps recognise the strong intangible bonds, connections, aspirations and motivations that eventually are able to inform a more inclusive design for a sustainable solution.

The informal sector is commonly (mis)understood as a problem. It is only described and defined in terms of data such as the size or the volume of material it handles, or the unsound environmental practices it uses. It is important to recognize that these are people who engage in e-waste dismantling for decades now. They have grown organically through scrap trades well before any legislation for e-waste processing was put in place. They developed mechanisms, skills and established a network to collect and dismantle e-waste to extract value from it, in exchange for a livelihood. The businessmen and workers here understand that change is inevitable, more so in the post-pandemic. We believe it is necessary and important to understand the changes as the community would like to see, from their own perspective, on the idea of dignity, prosperity, safety and a secure future.

Our first step in building trust and a relationship with the community was identifying local people who were interested in working with us as representatives of their community. Our continuous engagement both on-site through meetings and discussions and off-site through WhatsApp conversations & zoom meetings helped us to gain a better perspective into their lives. And eventually, soft drinks and platters of biryani and salad were served in many Community Representative’s (CR) homes and workshops which became our usual settings for meetings and discussions. The CR’s would bring their own confidants from the community to join us for these gatherings making a group of 5 turn to a group of 20 within minutes of invitation.

Glimpse from one of my first meeting in Seelampur in a dismantler’s unit.

Mapping challenges

While the e-waste micro-businesses support the local economy, provide jobs and livelihoods, directly and indirectly for skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled workers as service providers, their work is often not valued and negatively perceived due to their illegal and polluting work practices. Some of which include, unsound recycling practices, unsanitory working conditions, marginalisation of sector, little benefits and high requirements for formalization, economic and material losses and more.

While it may appear that we got access to the community quite easily, we must share that this has been challenging. Although we have a strong link and point of access through a team member who comes from and lives within this community, for the dismantler their time is valued by every kg of e-waste dismantled/ traded, and hence time equaled their daily wages. Arranging meetings came with extended wait times and we had to be more accommodating of the end-users even if it meant stretching timelines and deadlines.

Understanding networks, economies and business model

While it was important to understand the community socially and culturally, in order to bring value to the existing system, it was important to study and understand the routes and flows of e-waste not only in and around Delhi, but from across India. In an intensive workshop (held between the E[co]work Team and CSDC Team), Maps of India and the NCR were prepared, onto which material flows and existing networks were traced out. Further, we continued to add technical data and insights to these maps through information we gathered while directly engaging with the community over many months.

The dismantling business model is heavily dependent on point to point transactions within the region, with the price of goods increasing as they get processed along the way. Further, to run, one business requires about 2-6 people at a time. The skilled labourers are paid by the kilogram (kg) of material dismantled and sometimes a monthly salary.

Below is the video by the founders of E[co]work talking about the concept of E[co]work and our participatory process with e-waste dismantlers.

Design Charcha on visualising space

For this workshop, we brought together 15 micro-entrepreneurs from different neighbourhoods, with the intent to share various avenues that they as a community can take in order to run their business, while the sector begins to shift from being informal to formal. We also used this opportunity to acknowledge and help recognise that they are contributing to society and the economy of this country. We also shared systems that other countries have adopted to combat the problems that this sector faces.

The design workshop ended with a participatory activity where individuals were asked to “reimagine their space of work”.The venue of the workshop added to this experience because it was one of the potential spaces where the concept of E[co] work could be envisioned. With tapes and chalk as tools, the dismantlers present at the workshop divided themselves in groups of 3 and 4 and started visualising it.

They divided these space into how their existing spaces functioned, such as storage area, weigh bridge area, dismantling area and more. They designed it in a way, that the sizes of these areas were increased to make it less cramped and added CCTV cameras as a security element around the space. Along with it, they added rest areas for the dismantlers, a personal washroom (that is a luxury in these compact communities) and an open garden space with natural lighting. They also added an area for emergency exit just in case there is fire or unforeseen accidents. The outcomes offered insights into what they truly value in their place of work and also brought attention to things they care about.

Covid-19 pandemic impact

Whilst engagement activities were initially conducted in-person, often within dismantling units over tea and snacks, this had to cease with the increasing severity of the Covid-19 pandemic in late 2020, and use our online tools instead. The localised and often stringent lockdown measures brought the sector to a standstill as micro-entrepreneurs were no longer able to work.

Local lockdown restrictions excluded operations in industrial areas, causing dismantlers operating out of residential zones to understand the direct business continuity benefits and health benefits that moving to an industrial zone could bring. This unexpected benefit and piqued interest kick-started activities in this work package. More aggressive enforcement against polluting activities in the inner city areas has meant that the dismantlers increasingly face business closure (locally known as sealing) by enforcement agencies. The tense political environment due to the farmer protests and resulting transport and movement restrictions has added to the loss of work as the Delhi borders were shut.

Image 1: Screenshot from one of our calls with the Community Representatives from Seelampur and Mustafabad.

Image 2: Screenshot from another call during lockdown where we are all showing each other what our view from the window looks like.

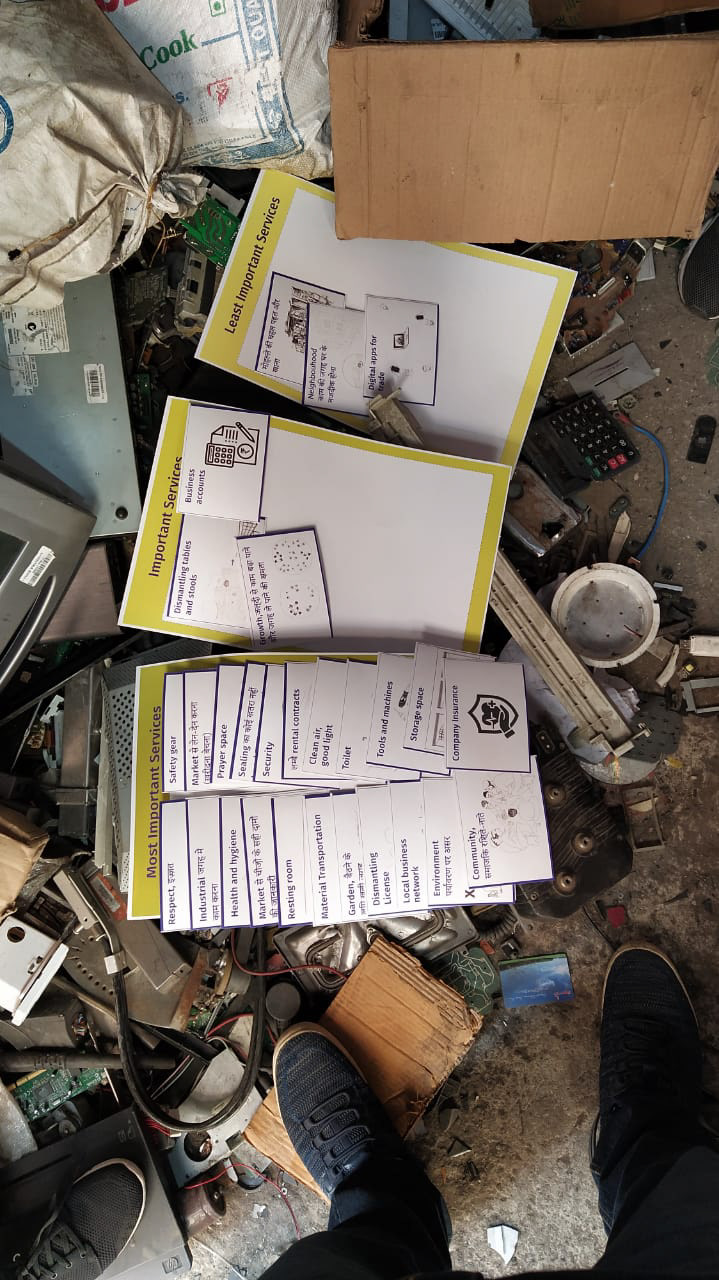

Design Charcha#2 / Essential services

We resumed our engagement with the e-waste micro-entrepreneur community in the two neighbourhoods of Seelampur and Mustafabad in November 2020, following the easing of Covid-19 restrictions in India. The intent of these visits was to learn about their key concerns regarding working in the proposed E[co]work facility and their preferences for services that may be offered in the facility. These findings helped us identify key attributes needed to develop a viable business proposal for the E[co]work pilot.

The aim of these activities was to help participants visualise their business as part of E[co]work and to nudge them towards thinking about best practices, rather than just market considerations.

The exercise demonstrated the dismantlers’ desire to benefit from the formalisation of some aspects of their work. They regarded operating in an industrial area with the necessary dismantling licenses, legalisation of their business and the ability to work without the fear of law enforcement curbs as some of the ‘most important’ service attributes. Having access to existing market and business networks, business expansion opportunities and proximity to their residence were also considered essential and ranked similarly. These considerations guided our search for locations suitable for establishing the pilot facility. Contrary to the pay as per use concept, the dismantlers preferred to have long term rental contracts in the facility. However, this was on the condition that their rents would stay comparable to what they currently pay and that there will be no adverse impacts on their productivity or access to existing markets and business networks.

Design features such as a dedicated prayer space, accessible toilets and ample storage space were also ranked ‘most important’. They were preferred over features such as access to clean air, good lighting, open space with gardens and having a resting room on site. These were not considered essential and accordingly ranked ‘important’. Working with dismantling stools, tables, the availability of appropriate tools, health and hygiene considerations and security features were also ranked ‘important’. This indicated that despite their initial reluctance to changing current work practices and habits, the dismantlers were willing to try out alternate ways. Other features such as having business accounts, considerations around their work neighbourhood and having a feeling of community with their colleagues in the facility were ranked ‘least important’. Additionally, they mentioned more services that they considered most important such as, travel services from home to E[co]work space, 24 hours open warehouse ID cards for all stakeholders (from transport to businessmen to labourer), Electricity, similar rents as the informal spaces.

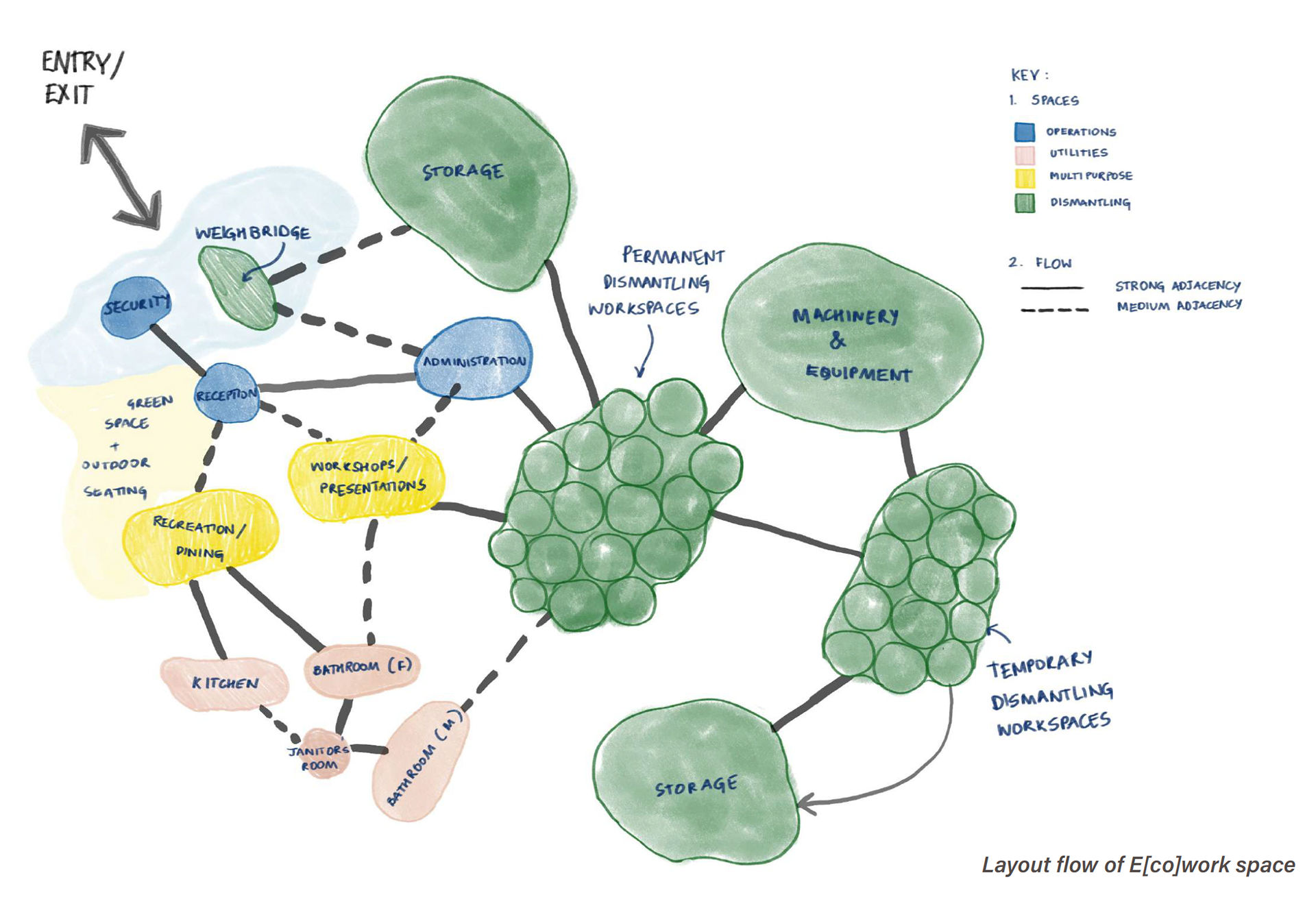

Design of E[co]work space

Building off these insights, this design process prioritised meeting the expectations of the dismantlers with nationally and internationally accepted guidelines and best practice for e-waste dismantling. Under the E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2016 (refer here), the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has prepared legal guidelines on extended producer responsibility, environmentally sound dismantling and recycling, collection centres, storage, refurbishment, channelisation, transportation and random sampling for RoHS (Restriction of the Use of certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment) testing. We made sure to follow these guidelines as well in our design process.

Based on our research and routine consultation with the dismantlers and the E[co]work team, several design options were shared. You can view the concept design in the below reports.

To learn in depth about the research, methodology, insights and challenges please do through these reports.

Click here to view:

The E[co]work space is now in process of construction with another team of architects.